WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. — Seventy-nine-year-old Bill Raftery is craning his neck and training his eyes on the 7-foot-4, 300-pound Boilermaker behemoth before him.

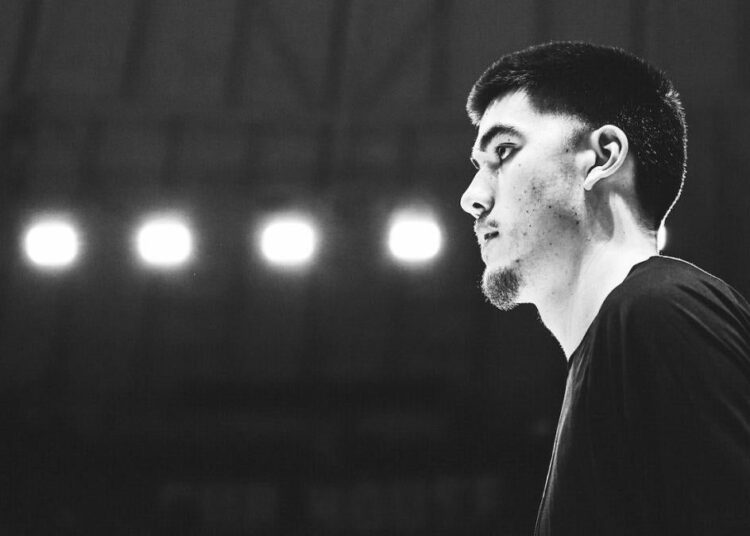

Zach Edey, top-ranked Purdue’s junior center/runaway leader for national player of the year, is on the receiving end of Raftery’s postgame interview treatment on CBS after what he’ll later say was the best game of his career so far: a personal-high 38 points in addition to 13 rebounds in a 77-61 home romp over Michigan State.

“If you were an opposing coach, how would you guard yourself?” Raftery asks.

“I have no idea,” Edey says.

This latest showpiece from Edey is another sensational performance in a season larded with them. As the Canadian colossus turns for the locker room, the sound of Mom’s voice stops him.

Julia Edey has a gift for her oldest son. It’s a black T-shirt, the latest in her DIY line of merch. Julia and her friends have been making Edey-specific garb since Zach’s sophomore year. The shirt she tosses him is an update on a former design. The front displays Edey’s Canadian-inspired nickname: THE BIG MAPLE. Edey puts the shirt on and a throng of fans courtside at Mackey Arena cheer in approval. As he turns and shows his back, the emblazoned message is a sendup to a thinning crowd of skeptics who’ve been bleating that Edey’s only been this productive, this good, because of his height.

Canadian charm and all, the shirt reads: He ain’t just tall, eh?!

And he’s not just another good college hoops player, eh! Edey is the sport’s best in 2023. A phenomenal thing considering he didn’t start playing basketball until a little more than five years ago.

Edey’s not just a huge deal because of his size. He’s been the frontrunner for national player of year since November; his ascent to the top is a staggering rise, a markedly different story from other college greats of the past 10, 20, 30-plus seasons.

When Edey got to Purdue, there was no big plan for the big man. After reclassifying from the 2021 class to 2020, Boilermakers coach Matt Painter considered redshirting his raw freshman. Even though he was shy on experience, Edey still showed enough. Too tall, too hardworking, too … Purdue to keep on the pine for a year.

Painter thought Edey would grow into a good player deeper into his college career, but nobody — not even Edey — imagined this level of supremacy over the sport.

“If you had told me coming out of high school,” Edey said, “I was going to be the national player of the year conversation as a junior, I would have laughed and said thank you for the compliment but I don’t know if that’s gonna happen. But now I’m here and I’m doing it, it’s surreal. That’s the word. Living through it is a surreal experience.”

You’re not supposed to be this good this fast, particularly if you’re 7-foot-4. Late bloomers, especially big men who didn’t grow up playing at an early age, usually slip incessantly along basketball’s steep learning curve. Edey’s broken the curve altogether.

“I enjoy when people doubt me,” he said. “That fuels me a little bit. Even now some people are doubting me. They don’t like the way I score the ball. Because I’m not hitting people with, like, the fancy moves or whatever. People have a problem with that. I believe as long as you’re putting the ball in the basket, it doesn’t matter how you do it.”

At 20 years old, this modest force of nature is getting visibly better by the week. For as great as he’s been, there remains the terrifying possibility for the rest of college basketball that Edey could be even more powerful by March.

“Everything’s kind of been gravy for him,” Painter said. “He just keeps getting better.”

If Edey goes on to win national player of the year, he might well be the only player to ever do it after playing just three seasons as a full-time starter in the entirety of his basketball life to that point.

“It’s a new love, it’s like having a new girlfriend,” Purdue assistant Brandon Brantley said. “That’s what basketball is to him.”

Edey was the 440th-ranked player in his class. There was almost no publicity attached to his recruitment. His teammate, David Jenkins Jr., has had a longer career playing college basketball than Edey has played organized basketball for his whole life.

“It’s a good example for a lot of people because he doesn’t have that baggage or that pressure of being that kid at 14, 15, 16, then all of a sudden you’re 21 and you’re good — but you’re not great — and everybody goes, ‘What’s wrong?'” Painter said. “Well, nothing’s wrong. It’s competitive. It’s hard to be good. It’s hard to get to that next level. But when you’re 14, everybody thought you’d be in college for a year or whatever. So he kind of plays pressure-free.”

He is a big man’s big man. Proof that, yes, they do still make ’em like they used to, when back-to-basket centers were the game’s irrepressible monsters, freaks of nature that added to basketball’s appeal.

“You look at other players, they can get 38 and they’re doing [crossovers, stepbacks, between-the-legs] 3s,” Edey said. “That’s never something I’m going to ever do. I stick to a few moves. I really really feel comfortable and I keep it simple. I’m never going to have that one-on-one flashy move, I’m going to use my size, my physicality, my strength to try to power through people.”

Edey’s averaging 22.4 points (fourth nationally), 13.4 rebounds (second), 2.2 blocks and shooting 62.7%. He’s attempted 800 field goals in his Purdue career and not one is a 3-pointer. (Edey’s never shot a 3 in a game in his life.) His Player Efficiency Rating currently registers at an absurd 41.7 — the best ever in college basketball, according to Sports Reference, even better than Zion Williamson’s record-setting 40.8 year in 2018-19.

He has an excellent chance to finish top-five in both scoring and rebounding. If he does that, he’ll be only the fourth player in the last 20 years to do it, joining the likes of Kevin Durant and Michael Beasley. He’s basketball’s best offensive rebounder, snaring 22.8% of Purdue’s miscues. At that rate, he’ll claim the second-best offensive rebounding season of the past two decades, but he’s still capable of catching DeJaun Blair 23.6% mark at Pitt in 2008-09.

Edey’s pacing to have the most 30-and-10 games by a high-major player in 20 or more years. What’s more, the big dude isn’t bloating his stats against the little guys: Edey is just as good against really good teams as he is the rest of the schedule, averaging 23.7 points and 12.6 rebounds against Purdue’s 11 best foes.

It wasn’t so long ago he was viewed as an off-the-bench novelty. Edey had a couple of good showings but was also erratic as a freshman.

“He turned the ball over, he elbowed people in the head, just the inability to have a feel for his surroundings,” Painter said. “Then all of a sudden it just stopped.”

“Everything that Coach Paint and Coach Brantley say, I try to take it in as much as possible,” Edey said. “Sometimes, some people allow success to make them think that they might be better than the coaching staff.”

Edey is referring to himself. He began his Purdue career by scoring 49 points in his first three games. Edey thought he had a lot of this D-I basketball stuff figured out. But an 11-game run of single-digit point totals awaited him. Edey admitted he “kind of almost stopped listening to the coaches and I thought I was better than them.”

“That was a big life lesson for me,” he said. “People will talk about playing through struggles … I think playing through success is almost as hard, not allowing you to get your head, keeping your head down, not listening to what people say — good or bad.”

Zach grew up with his parents and younger brother in the Toronto neighborhood of Leaside. Edey’s hockey days have become a recognizable part of his story (one NIL deal with Purdue includes hockey sweaters with his name and number). Leaside is an intense hockey community. Former Maple Leafs live there and an overwhelming majority of children are put on skates by age 5. Edey started late: 6.

By 8, he was playing in competitive youth leagues. He wanted to start at goalie but was too big, so he embraced being a defenseman. In addition to hockey, Zach also loved baseball, which his father Glen played growing up. By age 11, Edey was 6 feet tall. A year later, he was taller than his 6-3 mother. Young Zach often got told how he just had to play basketball.

That’s why he refused to do it.

“Sports are something special to me, sports are something that I choose to do,” Edey said. “I didn’t want people to force me into a certain sport where I didn’t feel like I was making the decision. I don’t think I would have been able to commit the way I have been able to commit if I had played as a 6-year-old.”

Edey was good at hockey but hung up his skates as he went into high school. He kept on with baseball into his teen years. Edey was touching low 80s on his pitches by age 15. Before that, he helped his team win three Toronto City championships while in middle school. In Canadian youth baseball, teams often field no more than 15 kids on a roster. Uniform numbers are made 1-15 according to size. The smaller the jersey, the smaller the number.

Zach had no choice about which number was his.

It’s why he still dons 15 to this day — a nod to baseball Edey brings with him to every basketball game.

Edey owes his Purdue career to his curious nature. After refusing basketball for years, he casually decided to play with friends as a way to cross-train for baseball. After he gave up hockey, Edey craved something in the winter that would keep him active. When he first tried basketball he didn’t enjoy it. Easily dunking over kids was boring.

“He needs to be challenged,” Julia said. “I think that’s why he didn’t love basketball when he first played.”

Zach hit 7 feet at 16 years old. He had to give up baseball after a shoulder issue affected his pitching; his enormous strike zone as a batter was also problematic. One unexpected basketball practice changed him. A father of one of his friend’s ran a local team. Zach showed up one day and found what he’d been looking for: a way for basketball to be hard. There was no scrimmaging that day; the kids hardly got up shots. Instead, Edey struggled through dribbling drills, then suffered through sprints for almost 20 minutes. He was exhausted.

He loved it.

‘Simple, but not easy’

How does a player go from barely knowing the sport in 2018 to being college basketball’s most important player in 2023? By sticking to a routine. A routine so important, it’s borderline maniacal.

“There’s no sexy answer to how I’ve done it,” Edey says. “I’m very constant with my work. I approach the game a very particular way.”

There is no wasted time. For Edey, everything is efficient. Repetition is paramount. The leaps he’s made haven’t been leaps at all — Edey’s progression has been one long Brobdingnagian stride after another.

He is a creature who thrives on good habits.

For the Edeys, life is about being humble, not seeking recognition as validation. Glen Edey earned money as a teen pumping gas. Julia Edey is a first-generation Canadian, one of five children to a pair of Chinese immigrants who owned a restaurant in the suburbs of Toronto. She worked in the restaurant as a teenager before growing up to become a mechanical engineer in the field of nuclear engineering.

“She knows all about hard work. She knows all about working even when no one’s paying attention,” Edey said. “My mom kind of grew up learning stuff on her own and she passed that on to me … I don’t like when stuff’s easy, I think I kind of feel like it’s a trap almost. I like my stuff simple, to know what I’m supposed to do, but I like working hard for everything I get.”

The great juxtaposition about this great big man is, for as loud as his stats are, he can be the quietest, calmest guy out there. Watch Edey play and you’ll see the biggest human in the building galloping back and forth across 94 feet of hardwood with a Zen-like calm for most of the game. His passion runs deep, rarely visibly rising above the surface.

“[My teammates will] think I’m having a decent game, they’ll look at the scoreboard and I’ll have like 17 and 10 at the half,” Edey said.

Edey’s regime has upped his stamina, which has been mammoth to handling getting the Shaq treatment, drawing more fouls than any player except UNC’s Armando Bacot. Unofficially, that mountainous body of his is on the receiving end of many more fouls that never get called.

“He’s got a tremendous inner toughness about him,” Brantley said. “Sometimes in this society, in basketball, we think toughness is standing in somebody’s face or talking to someone’s bench.”

Zach is often a taciturn competitor. But between the lines, he will take every opportunity to end you, a mentality that goes back to when his big right paw would swallow up a baseball.

“He was a closer and he absolutely ate it up because he loved that pressure to come in and save the game and get the win,” Julia Edey said. “Starter is a glory position, but as the closer he’d go still and shut it down.”

Another component to Edey’s greatness is how fit cultivates a player’s potential. He went to the right school with the right coach. It’s not hard to envision him going somewhere else, with a coaching staff on a different plan and pulling at the wrong threads, turning Edey into something he doesn’t want to be.

“He runs deep and he’s kind of quiet, but he’s very present,” Julia Edey said. “You need to be there with him. You don’t pull at him, you don’t pry at him, you just be there with him.”

She said a few of his former coaches have tried to “unlock the puzzle” that is her son, but that complicating the game for him or trying to expand beyond what his skill set obviously is was a recipe for a letdown.

“I like things that are simple, but not easy,” Edey said.

“If it’s easy, he’s going to be bored,” his mom said. “There’s a lot of deliberate analysis that occurs when he’s thinking about things.”

Edey needs to be pushed, but pushed with honest intentions. He is smart and has a good detector for bullshit.

“He has an ego and he believes in himself, but he doesn’t have this ego where ‘I gotta get 25 and 15 every night,'” Painter said. “But he just doesn’t have that (ego). He just doesn’t.”

Painter, who ranks among the brightest minds in basketball, has always let Edey develop at his pace and understood the man’s course. Edey’s lack of experience has been used as an enhancer, not a detriment.

“He doesn’t have the bad habits of someone who’s played since they’re 5,” Painter said.

As for his cherished routine, Edey always naps before games and always has to eat sushi. In warmups, his repetitions are the exact same every time, from Mikan drills to layup lines, foul shots and more. Routine affords comfort which induces the right headspace. Enter the Zen.

And there are the film sessions with Brantley, who has been Painter’s Big Man Whisperer for a decade. Brantley did not realize what he was getting himself into when he met Edey. Brantley gave him the customary, “Hit me up anytime you need anything.” For Edey, it was literal. He would message Brantley late at night, asking to meet him at the practice facility. On multiple occasions Brantley’s ducked and dodged Edey at the end of a long day because his wife wants him home and Brantley knows Edey will easily go for another hour to watch film if he sees him.

After each practice, it’s a minimum of 30 minutes of solo workouts every time. Edey works on hook shots by the hundreds, taking at least 10 from 12-15 spots on the floor. Right hand, left hand, over and over and over. On the road, there have been a few times where Purdue wasn’t close to a gym to get shots up before a game. Edey’s had team managers Google Map gyms to drive him to so he can get his drills in.

“Him not being able to do his routine is the equivalent of you and I not brushing our teeth that day,” Brantley said. “His dedication is unbelievable.”

Edey is such a fascinating player in the modern game. He’s ultra productive despite lacking athleticism and fine-tuned skills. But he has superb touch, his hook shot is dependable and his drop-step is used to increasing maximum effect. Baseball and hockey honed his hand-eye coordination, which plays a part in why he’s more dexterous than most oak trees in college basketball over the past 10-15 years.

“You can always hope to have a season like this, but it’s different living through it,” Edey said. “I don’t know if it’s surprise, I don’t know what it is, but there’s definitely some type of emotion like that. … I’m almost proving to myself every game that like, yeah, I am this. I’m doing this.”

The best compliment that can be paid to Edey’s game is how he’s managed to incorporate the intangible factor that so many great players bring onto the floor: so often, he can make it look easy — or simple. But that grace is inspired by a burn that has no chance of cooling over the next two months.

“He’s got an enormous chip on his shoulder,” Brantley said.

Brantley remembers watching ESPN in the first days of this season. On the screen was a segment about the best bigs in the country. There were five names on it: Tshiebwe, Timme, Bacot, Jackson-Davis, Dickinson. Edey wasn’t there. He wasn’t even brought up.

“He remembers that,” Brantley said.

And he hasn’t let it go. College basketball’s big friendly giant got overlooked, has been terrorizing everyone since and it’s put Purdue on a path to potentially one of its best seasons in school history.

Read the full article here