There’s one small corner of the world that Michael Jordan cherishes more than any other — his own personal haven of sporting bliss.

But it’s not in Chicago. In fact, there isn’t a basketball court or hoop in sight.

Even as he was staking his claim in the 1990s as the greatest player the NBA has ever seen, the Bulls icon was a regular guest on the golf course. These days, though, he hosts.

The Grove XXIII – a nod to his signature No. 23 jersey — is Jordan’s very own golf paradise, a private club tucked away on the outskirts of Hobe Sound, Florida. Ultra-exclusive, few have seen it, and even fewer have played it.

For Bobby Weed, it was at once the most straightforward and most difficult brief he had ever received: “Build me the best golf course. Build me the best driving range.”

And there had been plenty of briefs before. A protégé, then close friend, of legendary course designer Pete Dye, the South Carolinian served as the PGA Tour’s chief architect before launching his own course design company in 1994.

Almost three decades on, Bobby Weed Golf Design has sculpted more than 20 courses from the ground up – from Stillwater, Minnesota, to Mito, Japan — and renovated many more, including Hobe Sound’s Medalist Golf Club in 2015.

With Tiger Woods headlining a member’s list that reads like a who’s who of the game’s elite, the Medalist is a private club that attracts a star-studded cohort of visitors. Among them was Jordan, a keen admirer of the revamp and who, in late 2017, was on the hunt for a course architect.

A meeting later, Weed’s team was signed on to construct a golf kingdom fit for “His Airness.” As one of history’s most famous athletes, and with a net worth edging towards the $2 billion mark, according to Forbes, Jordan was a special category of client.

“I knew that it would get a lot of attention because of MJ,” Weed, 68, told CNN.

“I knew that there was some fanfare associated with it and I didn’t want to let him down.”

The land was secured soon after, some 200-plus acres of former citrus grove, next to Atlantic Ridge State Park. As he often does for projects, Weed lived on site, making the 265-mile switch across the state from Ponte Vedra Beach.

Weed was all-in, and encouraged Jordan to be as engaged as he wanted to be in developments, inviting him to come out once weekly to track the progress. Jordan often visited multiple times a week.

Weed likens his role as course architect to that of a quarterback: calling plays for a large roster of consultants. Watching Jordan in discussion with the team during one early meeting, he got the impression of a coach interacting with his players.

“I think one of his qualities is he was such a good listener, and he absorbed everything that you were discussing,” Weed said.

“He didn’t come out and say ‘do this or do that.’ He came out and observed and was a great listener, and he let me do my job.”

Weed had his two pillars for a great golf course — an engaged owner and a good piece of property, though the latter would require some polishing.

Turning a flat, “featureless” site – bordered by two long drainage canals – into a cross between the manicured, parkland style of Augusta National and the rustic layout of Pine Valley represented the greatest challenge to him and his team.

Dirt was excavated from lagoons to build the course and its features, fixing the flatness issue and leaving behind six large lakes – the same number of NBA Championships Jordan won. It was a coincidence, but ultimately fit the theme of a course tuned to the finest degree to its owner’s style.

Jordan wanted firm and fast, a course that could both excite and challenge its members, many of whom would be among the PGA Tour’s current stars. A double-helix layout, with a “crossover” at the 5th and 14th holes, offers the flexibility to play continual internal circuits in three, six, or nine-hole loops – ideal for Jordan’s busy schedule.

The course didn’t just need to suit the playstyle of its owner, though, it needed to enhance it.

“You don’t think I’m going to spend this much money and not have a little bit of an advantage do you?” Weed recalled Jordan saying.

Add to that the five-time MVP’s penchant for wagers, which will be familiar to viewers of docuseries “The Last Dance,” and the course has earned a new name among some members: “Slaughterhouse 23.”

“It’s his golf course, so it’s set up very well for him,” former world No. 1 Rickie Fowler told the Subpar podcast in 2020.

Weed, too, got drawn into the wagers, even during construction.

“I can remember us being out there hitting shots and doing a little gambling while we were just playing in the dirt. It was just great fun and interaction,” he said.

“It’s hard not to go out there and play a round with MJ without having a friendly wager.”

To meet the second requirement of Jordan’s brief, Weed’s team set aside 20 acres to construct a state-of-the-art practice facility that the designer believes has no equal.

Two 400-yard, double-sided driving lanes can be maintained for specific conditions, such as US Open or PGA Tour style fairways, with “target greens” in 25-yard increments. Each green has built-in pods that can track swathes of shot information, incorporating the PGA Tour’s ShotLink data.

The putting green is split into four quadrants, with incremental slopes ranging from 0-1% to 3-4% inclines. Even the grass on the tees is customizable, with different types to mimic warm or cool seasons.

“It’s a Tour player’s haven to work on their game,” said Weed.

Compared to Bobby Weed Golf Design, Nichols Architects had considerably less experience in golf courses, but it did have one key advantage in its efforts to beat other bids to build The Grove XXIII’s clubhouse.

Specializing in hospitality, residential, and commercial design, the firm had worked on the W South Beach in Miami — the favorite hotel of Jordan’s wife Yvette Prieto.

The team pulled no punches with its pitch to Jordan. “You’re not going to confuse this clubhouse with a clubhouse down the road or anything like that, and that’s what we’re selling you,” planning and design partner Igor Reyes told CNN of the pitching process, likening it to that depicted in the “Air” movie, where Nike must lure a rookie Jordan away from a deal with Adidas.

“You’ve really got to make an architectural iconic shape, and a shape that you could almost immediately feel was swinging across the landscape. Hopefully you can almost read the concept without anybody having to tell you,” Reyes said.

The deal clincher — outlined to Jordan in a pitch video — was that clubhouse shape, inspired by the smooth, “almost machine-like” perfection of a golf swing.

Reyes said his team had heard of Jordan’s purported early struggles with his swing, and, in the video, set up a column grid to map the building’s structure onto Tiger Woods’ club trajectory. Jordan was captivated, and told the firm there and then that it would get the contract.

“The first time you walk into the room with him, you don’t want to get too close or anything like that, it was kind of an odd thing,” Reyes said. “But by the second or third meeting we were just talking to him like a ‘regular’ client with a huge amount of respect.

“There was a really a sense of, ‘This isn’t just a guy with a lot of money that wants to do something. This guy knows what he’s doing, he knows what he likes, and how to get to it.’”

Inside, 15,000 square feet of space leaves ample room for men’s and women’s lockers, indoor and outdoor lounge areas, kitchen and dining facilities, and even a shop. Hospitality was a priority, with a below-ground level meaning all service, as well as golf cart storage, can be managed from underneath.

Like the course, Jordan’s identity was stamped all over. Columns were set further inside below an overhanging roof to mimic the hang-time that inspired the “Air Jordan” tag, while an elephant print used on some of his shoes was incorporated into the fritted-glass roof, casting the print across the floor when the sun shines through.

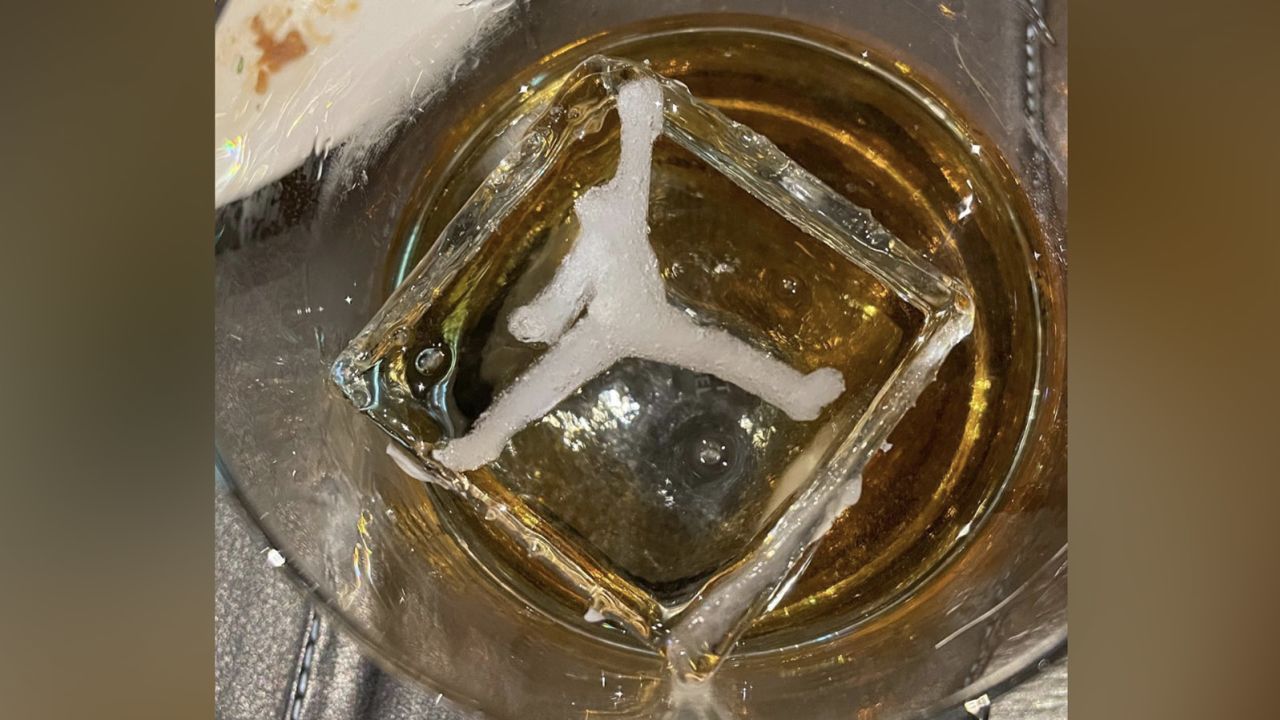

Customization goes all the way down to Air Jordan logos on the ice cubes, as PGA Tour pro Jimmy Walker shared to Instagram after a round at the course in March 2021.

Like Weed, Reyes believes his job was made easier by an engaged client.

“He was involved with a lot of the decisions … we didn’t change a color without him knowing,” Reyes said.

“We have had work with other celebrity people and they won’t talk to you, it’s ‘I just want this’ and sort of like, ‘get out of the way.’ But he realized there was a lot of creativity going on and he wanted to be a part of it.”

Given Jordan’s regular on-site visits, there was no big reveal for the owner when the Grove XXIII officially opened in the fall of 2019, but there was a revelation when Weed joined him for his very first round.

When play finished, the architect found himself wrapped in a 6-foot, 6-inch bear hug.

“He looked at me and said, ‘I’m fortunate enough I can be anywhere in the world, but there’s no other place I’d rather be than right here,’” Weed recalled.

“That’s like the ultimate compliment … to have his own golf course and to shape and mold that golf course for him and his friends, it’s just where he wants to be. It’s just a great spot and evolved into something fantastic.

“He’s going to enjoy it as long as he’s playing and then it’s going to get passed along to the next generation — it’s just one of the great things about golf and why it has sustained itself over centuries.”

Read the full article here