Great Bambino … Sultan of Swat … steelworker?

Yes, Babe Ruth, the man who would hit 714 home runs in Major League Baseball had a stint as a steelworker early in his career. Why the move to working for Bethlehem Steel in Lebanon, Pennsylvania? The career change was a result of a US government directive during the first world war called the Work-or-Fight Order: Eligible men had to either register for the draft or find essential work – such as at a steel mill. But there was a loophole for Major Leaguers like Ruth. Bethlehem Steel had its own baseball league and was all too happy to hire professional athletes, ostensibly for war-related jobs but actually to enhance its league’s competitiveness. This story rises from obscurity in a book published earlier this year – Work, Fight, or Play Ball, by Pennsylvania-based journalist William Ecenbarger.

“We didn’t know how long the war was going to last,” Ecenbarger says. “There were concerns about being drafted. The obvious way out was to play ball for one of the shipyards or steel mills.”

Ballplayers who did so included not only Ruth but fellow greats such as Shoeless Joe Jackson and Rogers Hornsby. The list featured around 45 active Major Leaguers, as well as about 30 retired players.

Related: Babe Ruth’s ‘called shot’ jersey from 1932 World Series sells for record $24.1m

Bethlehem Steel had the money and motivation. Business was booming due to wartime orders to build ships that would transport troops to Europe. Owner Charles Schwab – no, not the financial-services guru – created the Bethlehem Steel League in 1917 to entertain his burgeoning workforce. Its six teams were originally composed entirely of steelworkers, but the Work-or-Fight Order sparked an exodus from the majors when it was issued in May 1918.

Most players went to the Bethlehem Steel League, with some joining the rival Delaware River Shipbuilding League, which was also linked to Schwab.

“It’s hard to generalize what the motivations of the players were,” Ecenbarger says. “I think some players genuinely wanted to participate in the war effort.”

Count Shoeless Joe in that category. Although the Chicago White Sox star would go on to infamy in the Black Sox scandal the following year, the Ecenbarger credits Jackson with showing up to his job as a painter and fundraising for the war effort on his days off. However, he adds, “The overwhelming majority, I think, wanted to avoid the draft, avoid going to France.”

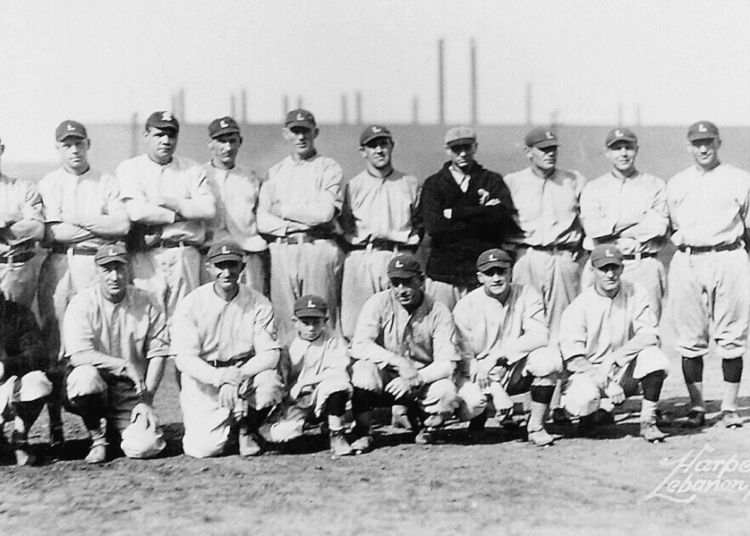

Ruth and his teammates on the Boston Red Sox had received a draft exemption thanks to playing in the 1918 World Series. So did their rivals, the Chicago Cubs. After the series ended in a Red Sox victory, Ruth joined the Bethlehem Steel mill in Lebanon, where he rented an apartment and bought a new Scripps-Booth roadster.

It didn’t hurt that Bethlehem Steel paid the ballplayers higher salaries than regular employees.

“I’m sure there was a lot of resentment among the regular workers,” Ecenbarger says. “It’s hard to document. There’s not a lot written about this league.”

The author lives not far from Lebanon. Thirty-five years ago, he was walking his dog past an abandoned turn-of-the-century amusement park. There was a sign nearby – “Babe Ruth Field.” He contacted the Lebanon County Historical Society: “He never played here, did he?” “Oh yes, he did.” The society had what it claimed was the Babe’s old jersey, adorned only with the words “Beth Steel” – there were no uniform numbers back then. The memory lingered in Ecenbarger’s mind. Several years ago, his wife suggested he write a book about the Steel League.

Ecenbarger checked out library biographies of the principals – including Ruth, Hornsby and Jackson – yet details on the Steel League were scarce. A trip to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum similarly yielded little information. Newspapers from 1917 and 1918 were more helpful. With baseball supreme as the national pastime, still unchallenged by football, basketball and hockey, and with print journalism the main source of media, the exhaustive game summaries proved invaluable.

The book explores the complex role of baseball within American society after the country entered the war. According to the author, Americans were pressured to “do one’s bit,” and those reluctant to do so were labeled “slackers.” Players participated in mock military drills at ballparks, using bats instead of rifles.

There were Major Leaguers who joined the war effort. Ecenbarger puts their number at 250, noting that they included eventual Hall of Famers Ty Cobb, Christy Mathewson and Grover Cleveland Alexander.

“Cobb was considered the game’s greatest player,” Ecenbarger says. “He had three young children and a deferment and enlisted anyway, into a unit that was one of the most dangerous in the army,” the Army Chemical Warfare Division, which “defended against poison gas attacks … It was dangerous for Christy Mathewson, who served with Cobb and was gassed in France. It ended his career. Grover Cleveland Alexander, the Cubs’ star pitcher, missed the World Series because he was in France.”

Shoeless Joe Jackson had three brothers serving in France. He was married and had two other siblings and a widowed mother depending on him for their livelihood. In the spring of 1918, Jackson’s South Carolina draft board took away his exemption.

“Other Major Leaguers said, if they can draft Joe Jackson, they can draft anybody,” Ecenbarger says.

Jackson set a precedent by leaving the White Sox for a Bethlehem Steel subsidiary – the Delaware-based Harlan & Hollingsworth Shipbuilding Company. He suited up for his new employer’s Wilmington team.

“Shoeless Joe Jackson at one point said it was harder to hit in the Bethlehem Steel League than it was in the American League,” Ecenbarger says. “The quality of the ballplayers was very high … teams around central Pennsylvania and Wilmington would often outdraw the Philadelphia Athletics and Philadelphia Phillies.”

Throughout that summer, Ruth held on to his job with the Red Sox. At the time, he was known as a standout pitcher, not a power hitter. The war and the Steel League changed things. As teammates departed for one or the other, the shorthanded Red Sox put Ruth in the outfield. At the plate, he dazzled with home-run pop, a rarity for the era.

In the World Series, Ruth pitched a shutout in Game 1. Befitting the national patriotic sentiment, the Star-Spangled Banner was played during the seventh-inning stretch. Ruth saw his record Series scoreless-innings streak end in Game 4, but he and the Red Sox won the championship. Then he prepared for his new “career” as a steelworker – specifically, a blueprint messenger.

Ruth didn’t deliver any blueprints while on the Bethlehem Steel payroll. He ended up playing just one exhibition game for Lebanon. In the eighth inning, he came up to bat with nobody out and runners on second and third. He drew an intentional walk, dismaying the crowd, and the pitcher got out of the inning.

Ecenbarger interviewed two locals with memories of Ruth for a Philadelphia Inquirer Sunday magazine article in the late 1980s.

“Both told me Babe Ruth didn’t do any work at the steel mill,” Ecenbarger says. “He came to the mill dressed in expensive clothes and talked to people about baseball for one hour, then he would leave.”

Other ballplayers made plans to follow Ruth to the Steel League, while the majors decided to cancel the 1919 season.

“The players on the Red Sox and Cubs … after the World Series, [they] started moving into the Bethlehem Steel League,” Ecenbarger says. “Everyone thought the war would go on.”

Instead, the conflict ended in November. The 1919 season was back on schedule, and that year, the Steel League folded while the majors experienced a new attendance mark.

“Some people wondered what they would do with players who jumped to the Bethlehem Steel League,” Ecenbarger says. “Some suggested they should be barred from baseball for ever. The owners realized they really needed their star players back. Everyone came back.”

Jackson was eventually banned from baseball for life – not because of the Steel League, but rather his participation in the Black Sox scandal.

“He didn’t realize some of the things he did were not going to be popular,” Ecenbarger says. “He was easily misled.” But, the author adds, “From everything I read about him in the shipyard and steel [mill], he worked and worked hard … He really did try to participate in the war effort – ‘do his bit,’ as they say.”

Read the full article here