It has been difficult to watch Erling Haaland squander his early promise. It would be perverse to criticise his first season in England, a one-man mockery of the idea that adapting to the Premier League takes time. Haaland has been so good that fantasy football bores will name children after him.

Somewhere along the way though, something was lost. Before City, Haaland was a wonderfully brusque interviewee. He had a Norse impatience with appearing on camera which matched his on-pitch demeanour, a man bored by his own outlandish gifts, like one of the feckless children of Logan Roy.

When Haaland speaks now it is in an identical register to his tactically interchangeable team-mates. Bit of humour, bit of humble, hearty laughs all round then off into the night. He is another perfect cog in City’s winning machine, but in a team of Noels he should be a Liam.

As with Oasis, Haaland’s early stuff is still the best. He once scored a first-half hat-trick in the Champions League while still with Energy Drink Salzburg. How did that feel, he was asked.

“I feel very good.”

“Anything else?”

“You ask how I felt, I answered.”

After a pandemic game for Borussia Dortmund he went over to salute the empty south stand, where Dortmund’s yellow wall would have been. Why?

“Why not?”

“Is there a kind of message you want to send out?”

“Yes.”

Of course it is one thing to do this in the German and Austrian Bundesligen, where interviewers allow an extra split second you simply do not get when up against Geoff Shreeves. But it still feels like a let-down that Haaland’s only memorable interview to date for City involved swearing, then apologising and saying the same word again while doing so.

Otherwise it has been bland business as usual. There was a masterclass on CBS, arriving post-game at pitchside podium, shaking hands with Jamie Carragher, Thierry Henry and Micah Richards then presenter Jules Breach, generously offering more than two words when asked, again, how it felt to score a goal, then segueing into a cheeky dig at Carragher and Richards. Textbook.

There was a credible attempt at a Barnsley accent when mocking John Stones’ pronunciation of the Louvre.

(Why is John Stones being made to talk about the Louvre? This never used to happen to Terry Butcher.)

Then during a gentle grilling by Gary Neville, Haaland revealed he likes kebab pizzas and wine. So, much as with his football, he has adjusted to the established way of doing these things at the top level: lighthearted and chronically unrevealing.

The marginally serious point is that we are watching an unusual person having his rough edges polished away. Haaland has to behave himself now he is in the Premier League, a platform which will not tolerate anything outside its pre-ordained strictures of weirdness, unchanged since the boundary-pushing era of Jimmy Bullard.

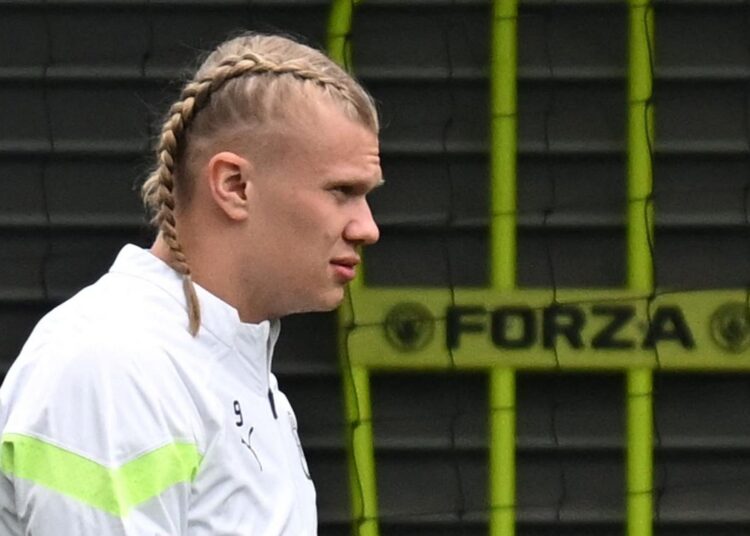

And Haaland is weird, without doubt. Look at him, the 90s action film baddy who gives Bruce Willis a run for his money before being vanquished in the final act. Physically he is unlike anything we have seen before, granite-sculpted but terrifyingly quick, strafing stiffly in penalty boxes like a Boston Dynamics robot dog.

Then sometimes he wears his hair in delicate plaits. When Neville asked him the three people he would take to a desert island he named Kevin de Bruyne, who will “assist” him (hur hur hur) but also, almost tenderly, his mother and father “to take good care of me and cook some good Norwegian food.”

On the pitch Haaland is as jolting as an electric shock, but off it now more like an electric blanket. Maybe he is happier at City, more mature, or did not love the optics of unsettling squirming interviewers. Maybe if City ever go through a period of genuine adversity some of the old edge will return.

For now he gives normal interviews that make him seem normal, which he quite obviously is not.

Read the full article here