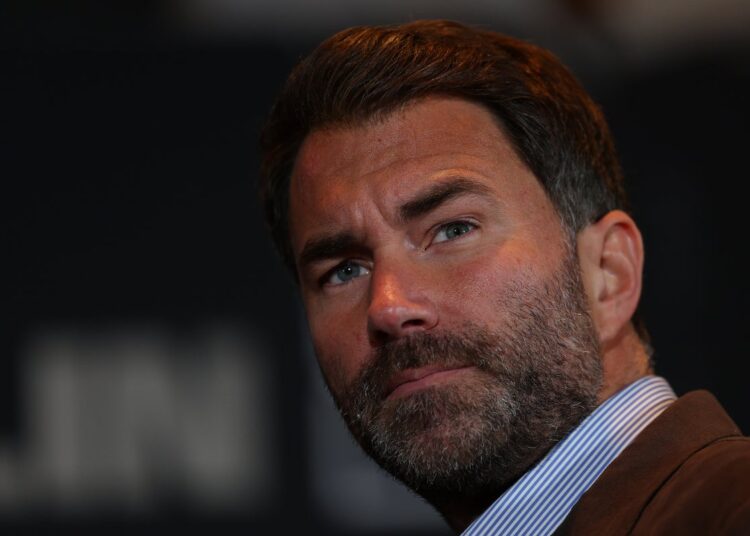

If you asked someone on the street to name three people in UK boxing, they’d probably go: ‘Tyson Fury, Anthony Joshua, Eddie Hearn.’ Or something like that – top five maybe. That’s important.”

Some may be irked by Hearn’s claim, but they’d struggle to argue against it. The promoter’s rise in boxing has been symbiotic with Joshua’s, but certainly not wholly reliant on it. Hearn himself has become a heavyweight, in a sense, and while his father – legendary promoter Barry Hearn – and “AJ” have contributed to that profile, so has the 44-year-old’s own approach to business.

“I think it’s my engine. Being a promoter is being a showman, a salesman, and no one sells like me – no one,” Hearn tells The Independent. He’s sat in breezy, linen clothing on the sizeable lawn of Matchroom HQ – a quasi-mansion on the outskirts of Brentwood in Essex, and a building that was his childhood home. On the odd occasion that he breaks eye contact, his gaze is pushing past the garden’s helipad and locking onto an unobscured London skyline. “Promoters are a dying breed. Everyone else has given up leading their own press conferences, pathetic. That is the purest skill of promotion: presenting your show.” That is, among other things, what Hearn does so well, and that is why his evaluation of his place in British boxing is so high.

“Academically I’m definitely not a genius,” he adds, “but my street-wise, common sense, work ethic won’t be beaten. I don’t claim to know a lot about many things, but what I do know about is boxing. I’ve been around it since I was eight years old.”

Hearn, like most promoters, is distrusted by many fans. In a sport where the biggest fights prove so elusive, the words of Hearn and his counterparts are often construed as mistruths or, at best, half-truths. That is understandable, yet when Hearn is in full flow, his tone, expressions and mannerisms emit a vibe that is distinctly anti-‘BS’. It is for you to decide, but there is one perception that Hearn is keen to contest.

“Maybe that I don’t care enough about the sport,” he says. “In this country, the support you get when you’re not always winning is unbelievable. But when you start winning, you’re almost viewed as the evil side. That’s a bit frustrating, because I genuinely love the sport more than anything. Sometimes I do things in the community, some you’ll hear about and others you won’t… I’m pretty selfish and driven as an individual, and there’s not many things that would make me put integrity first, but boxing is one of them.”

Hearn’s integrity has frequently been questioned over the past 12 months, largely due to his defence of Conor Benn in the wake of the young welterweight’s adverse drug-test results last year. Hearn chose to stay in the 26-year-old’s corner, admitting that he was risking his own reputation by doing so. While boxing faces what appears to be a doping crisis, Hearn points to the fact that his company, Matchroom, is at least willing to pay the substantial costs for anti-doping tests that many promoters are reluctant to entertain.

And ‘reluctant to entertain’ is a combination of words that would apply to Hearn in very few contexts. When the meme page ‘No Context Hearn’ took off on social media a few years ago, he was quick to embrace it – recognising how it may help his profile and, in turn, the profile of his fighters. “Probably 20 or 30 per cent of people know me from the memes, which is frightening, but it helps,” he says. “There’s still many people who think I started that page. The guy who started it is called Andy, he works for the NHS, and he said: ‘Look, would you mind?’ The next thing, it’s got thousands of views, and the younger generation is watching. I go to pick my kids up from school, and the other kids are like: ‘I’ve seen you on TikTok.’”

While those viral clips saw Hearn win many fans, he still has his detractors, of course. That question of integrity cannot be forgotten after a paragraph of text, and Hearn knows that it will not be quelled by his aforementioned work in the community. Still, he pursues those ventures for a reason, and it goes beyond ‘profile’. In fact, it stems from him questioning the integrity of others: namely, those in government.

Hearn is speaking to The Independent days after Matchroom paid the fees required to prevent the closure of the Lynn AC boxing gym – the oldest amateur club in the country, built in 1892. “I’m about to fully attack the government regarding funding for amateur boxing clubs,” Hearn says. “The government were prepared to let that place evaporate into thin air. It’s frightening. You talk about gang and knife crime; do you honestly think the people in power have any idea what can help in that respect? There is absolutely no question that taking a kid to a boxing club will improve their life.

“I don’t wanna be known as a philanthropist; I wanna be known as someone who convinced the system that this helps. They’re soul-cleansing experiences that make me realise why I love the sport, when the bulls*** end at the top might make me wanna walk away.”

Hearn has loose plans to walk away at 50 anyway, though that seems unlikely. He admits that he will “never” fully leave boxing, but acknowledges that doing so would give him more time with his family. “The last few years have been harder, because I’m away almost every weekend,” he says, reflecting on his relationship with his two teenage daughters. “The hardest thing is having the energy to go above and beyond when you’re there. But they know no different, just like I didn’t. My dad wasn’t around a lot at all, but I just remember how much he’d play with me – out here in the garden – when he was around. It was non-stop, and I just try and replicate that. If I’ve got three days with them and then I’m away for a week, let’s go: I’m all action.”

If that is one way in which Hearn tries to emulate his father, there are certainly ways in which he seeks to be different. “Definitely in my ability to absorb confrontation, criticism and disloyalty,” he says. “The amount of times he’s gone, ‘I can’t believe they’ve done that, tell them to f*** off,’ and I’ll go: ‘It’s calm, don’t worry.’ We’re both massive on loyalty, but you also have to understand the business you’re in. Sometimes boxers have to make a move that benefits their career and family; others won’t, and they’re the ones you look after forever, like they are family.

“I said to him the other day: ‘Can you imagine if you were promoting today, and I was your competition rather than your son?’ He said: ‘I’d f***ing stick one right on your chin. I couldn’t stand you.’ I feed off Frank Warren and those guys, and I’d feed off my dad, because I know all the bits that really get him. For me, it’s more of a game, and I don’t take things personally. I’ll say: ‘You wanna f*** me? No problem. I’ll remember, but good luck.’”

In any case, Barry offered his son a compelling introduction to boxing, one that shaped the younger Hearn’s life. The 44-year-old admits that experiences like spending a weekend in New York with Prince Naseem Hamed and hanging out backstage with Chris Eubank and Frank Bruno made it hard to focus at school, but they also inspired Hearn to pursue a career in promotion after first trying his hand at competing. “My dad made me fight under an alias,” he recalls. “It was my first fight, in Dagenham, and they introduced me as Eddie Hills. In the car on the way home, I went: ‘Ah, I can’t believe they introduced me as that.’ My dad goes: ‘Yeah, I didn’t want them to know you was my son, because you’d have got a pasting.’ They battered me anyway, so it didn’t really matter.

“I was just petrified… excited. I’m 13, 14, there’s carpet tiles on the ring… but that environment was my environment. Although I was a silver-spoon kid, as my old man always said, I grew up in that environment. I was at these shows from eight or nine, I was in the changing rooms, I was hanging around these fighters. I was seeing arguments, fights in the crowd around me. But doing it yourself is an unbelievable buzz. I was very average, but I thought I could fight, because I was hanging out with Nas’ and Eubank and Bruno and all these guys.”

And what those fighters were to Barry Hearn, Anthony Joshua has been to Eddie Hearn.

“He’s a one-off,” Hearn says. “Tyson Fury’s gone to great levels as well, but Joshua… We did a tremendous job with him and still do, but he was a one-off. Without him, I don’t think our business would be where it is today; British boxing wouldn’t be where it is today. He was just a diamond that appeared in the sport.”

That diamond still needed crafting, however. And whatever you think of Hearn, he played his part.

Read the full article here

Discussion about this post