This story, by senior writer Michael Knisley, first appeared in the March 6, 1995, issue of The Sporting News, almost six years after goalie Clint Malarchuk of the Buffalo Sabres suffered a near-fatal injury when his jugular vein was slashed by an opposing player’s skate.

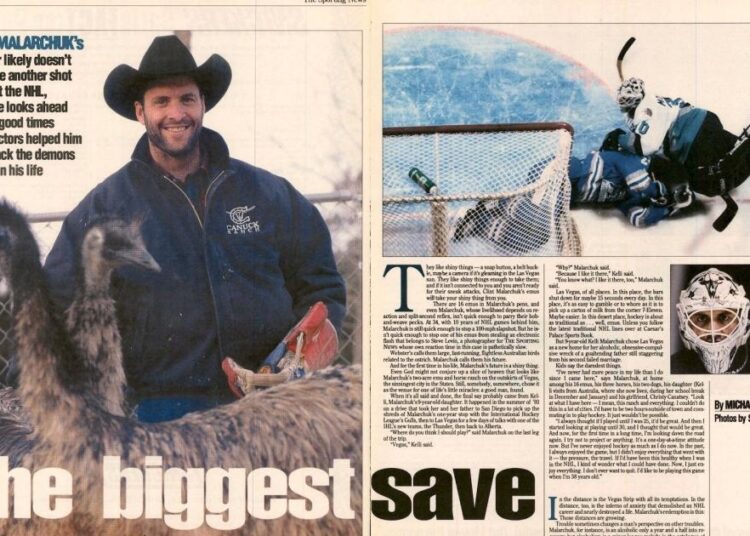

They like shiny things — a snap button, a belt buckle, maybe a camera if it’s gleaming in the Las Vegas sun. They like shiny things enough to take them; and if it isn’t connected to you and you aren’t ready for their sneak attacks, Clint Malarchuk’s emus will take your shiny thing from you.

There are 16 emus in Malarchuk’s pens, and even Malarchuk, whose livelihood depends on reaction and split-second reflex, isn’t quick enough to parry their bob-and-weave pecks. At 34, with 10 years of NHL games behind him, Malarchuk is still quick enough to stop a 10O-mph slapshot. But he isn’t quick enough to stop one of his emus from stealing an electronic flash that belongs to Steve Levin, a photographer for THE SPORTING NEWS whose own reaction time in this case is pathetically slow.

Webster’s calls them large, fast-running, flightless Australian birds related to the ostrich. Malarchuk calls them his future.

And for the first time in his life, Malarchuk’s future is a shiny thing.

Even God might not conjure up a slice of heaven that looks like Malarchuk’s two-acre emu and horse ranch on the outskirts of Vegas, the sinningest city in the States. Still, somebody, somewhere, chose it as the venue for one of life’s little miracles: a good man, found.

When it’s all said and done, the final say probably came from Kelli, Malarchuk’s 9-year-old daughter. It happened in the summer of ’93 on a drive that took her and her father to San Diego to pick up the shreds of Malarchuk’s one-year stop with the International Hockey League’s Gulls, then to Las Vegas for a few days of talks with one of the IHL’s new teams, the Thunder, then back to Alberta.

“Where do you think I should play?” said Malarchuk on the last leg of the trip.

“Vegas,” Kelli said.

“Why?” Malarchuk said.

“Because I like it there,” Kelli said.

“You know what? I like it there, too,” Malarchuk said.

Las Vegas, of all places. In this place, the bars shut down for maybe 15 seconds every day. In this place, it’s as easy to gamble or to whore as it is to pick up a carton of milk from the comer 7-Eleven. Maybe easier. In this desert place, hockey is about as traditional as … well, emus. Unless you follow the latest traditional NHL lines over at Caesar’s Palace Sports Book.

But 9-year-old Kelli Malarchuk chose Las Vegas as a new home for her alcoholic, obsessive-compulsive wreck of a goaltending father still staggering from his second failed marriage.

Kids say the darndest things.

“I’ve never had more peace in my life than I do since I came here,” says Malarchuk, at home among his 16 emus, his three horses, his two dogs, his daughter (Kelli visits from Australia, where she now lives, during her school break in December and January) and his girlfriend, Christy Canatsey. “Look at what I have here — I mean, this ranch and everything. I couldn’t do this in a lot of cities. I’d have to be two hours outside of town and commuting in to play hockey. It just wouldn’t be possible.

“I always thought if I played until I was 25, it’d be great And then I started looking at playing until 30, and I thought that would be great And now, for the first time in a long time, I’m looking down the road again. I try not to project or anything. It’s a one-day-at-a-time attitude now. But I’ve never enjoyed hockey as much as I do now. In the past, I always enjoyed the game, but I didn’t enjoy everything that went with it — the pressure, the travel. If I’d have been this healthy when I was in the NHL, I kind of wonder what I could have done. Now, I just enjoy everything. I don’t ever want to quit I’d like to be playing this game when I’m 38 years old.”

•••

In the distance is the Vegas Strip with all its temptations. In the distance, too, is the inferno of anxiety that demolished an NHL career and nearly destroyed a life. Malarchuk’s redemption is this: Those distances are growing.

Trouble sometimes changes a man’s perspective on other troubles. Malarchuk, for instance, is an alcoholic only a year and a half into recovery, but alcoholism is a minor league malady in the catalogue of misery that marks his life before Vegas. It’s an afterthought. Oh yeah, I’m an alcoholic, too.

Before the alcoholism came the jugular vein, which was severed in Buffalo on March 22, 1989, by a skate blade in a collision with the Blues’ Steve Tuttle. As Malarchuk’s blood squirted, with every beat of his heart, several feet out onto the ice in front of the net, he looked up at an official and said, “Am I going to live?”

He lived, but barely.

Before the jugular vein came the osteomyelitis, which nearly cost him a leg when he was 17. A basic knee operation to repair some tom cartilage turned into a staph infection that kept him in isolation in the hospital for two months. It went to the bone and looked to be spreading to the rest of his skeleton, which would have been fatal. Doctors decided on amputation if one last try at an antibiotic didn’t work.

It worked, in the nick of time.

And before, during and after the osteomyelitis and the jugular vein and the alcoholism came the obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), the most frightening of them all. It is the factor most responsible for taking Malarchuk out of the NHL after 10 seasons with Quebec, Washington and Buffalo, and into the minors. It is the most horrible hell he has faced, and it has come closer to costing him his life — on a number of occasions — than any of those other troubles.

The season he played in San Diego (1992- 93), for instance, a Sabres goaltender was injured, and they brought him up for three or four days as a backup and then sent him back down. The trip and the illness turned Malarchuk into a walking time bomb.

“I picked him up the night before he was going back to San Diego, and he was close to buying it that night,” says Chris Reichert, a friend who was the Sabres’ strength coach at the time. “I walked with him for four or five hours. He was obsessing. He was a mess. He was crying. He just broke down. After he got on the plane, I called ‘Duds’ (Rick Dudley, who coached Malarchuk with the Sabres and the Gulls) and told him, ‘I think Clint is going to die tonight. I think something is going to happen, so please take care of him.’ It was a real tough time for him.”

•••

We’re still learning about obsessive-compulsive disorder and how to treat it. Doctors think it is an abnormal metabolism in the brain, specifically involving a chemical called seratonin that helps transmit messages from one brain cell to the next. They’ve established that much only within the last decade. They’ve also established that every 40th person may have it, which is an astounding number for an illness so little-known. That makes it more common than asthma or diabetes.

But establishing all that hasn’t helped identify a universal cure for it. Behavior therapy, drugs, psychotherapy, cognitive therapy, electroconvulsive therapy — they’re all being tried. The medical literature still includes as a last resort in treatment of OCD the possibility of psychosurgery — lobotomy, in other words.

The bottom line is that different OCD sufferers react to different treatments in different ways. When the OCD sufferer is, say, an NHL goaltender, some forms of treatment — some drugs — are not only unsuitable, they’re also counter-productive.

“It’s very complex,” says Dr. Lee Rice, the director of the San Diego Sports Medicine Center and the team physician for the Chargers for 16 years. “When OCD is either undiagnosed or untreated, the symptoms caused by it cause all kinds of related concerns and fears. It can render the person, basically, totally dysfunctional. But what we do know about it pales in comparison to what we don’t know.

“I do know that many of the medications that can be very useful for this disease aren’t acceptable for professional athletes or anybody else who has to operate at a high performance level, because they can create either sedation or a slowing of reflexes. It makes it more difficult to treat professional athletes, because it decreases your options.”

Malarchuk found that out the hard way. For a time, he tended goal on Prozac, an antidepressant, which gave him the shakes. For a time, he tended goal on Haldol, an antipsychotic, which sedated him. For a time, he even tended goal in Buffalo on Orap, a major tranquilizer, in a treatment decision that defies belief.

“That’s normally given to treat schizophrenia,” says Dr. Stephen Stahl, an internationally known OCD expert in the psychiatry department at the University of California in San Diego, and one of the doctors responsible for Malarchuk’s recovery. “It’s given to people, basically, who are crazy. It creates a drug-induced form of Parkinson’s Disease. How well do you suppose you can play hockey with Parkinson’s Disease caused by a drug?”

Malarchuk knew he wasn’t playing hockey very well that way. But when he eased up on the medications for relief from the side effects, the obsessions crept back in.

Now, under Stahl’s treatment, he’s tending goal on Zoloft, another antidepressant, which is the miracle-worker in his case. But for the first six weeks of his treatment even with Zoloft, the side effects included nausea, diarrhea and deep depression. Try stopping a 101-mph s!apshot like that.

When a person with OCD is obsessive, he or she has repeated unwanted, intrusive thoughts or worries or impulses that often are unpleasant and senseless. Sometimes, the obsession is simple, involving germs or contamination, for example. Sometimes it defies logic, as when a person worries constantly that he or she forgot to turn the kitchen stove off, despite constant checks that it is off. And sometimes, the obsession is more serious — it can include repeated impulses to kill a family member or loved one.

A compulsion is a repeated action or behavior, usually in response to an obsession. Among the more common compulsions are repeated hand-washing, putting on and taking off clothes, or checking locks or the stove. Some OCD sufferers complain of problems such as irrational beliefs that they’ve injured someone in an auto accident, which requires that they repeatedly re-trace their route to check on the victim.

It’s sometimes called “the doubter’s disease” because those who suffer from it doubt even the most obvious realities.

“I could say this table is brown,” Malarchuk says, “I know it’s brown and you know it’s brown. But when you’re obsessing, you get stuck. You don’t believe it. You can actually say, ‘Yeah, I know it’s brown.’ But up here, in your head, it just doesn’t finish. You can’t finish your thought. It’s like stuttering. It’s the same sort of thing. When somebody is stuttering and he’s stuck, it’s not so much the physical part of the mouth not being able to finish the word. It’s a mental thing.”

There is a connection between OCD and Tourette’s Syndrome, which involves stuttering, or physical tics, or grunts or sometimes uncontrollable strings of obscenities. The Nuggets’ Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf and the Phillies’ Jim Eisenreich have Tourette’s Syndrome; Malarchuk has been diagnosed with Tourette’s in the past.

Malarchuk is, or was, more obsessive than compulsive. He didn’t often act on his obsessions, but they drove him to bottomless depths nonetheless – beginning when he was 12 and was hospitalized with severe anxiety problems. Then, he worried about his mother and his grandmother, with whom he was close. An alcoholic father abandoned the family when Malarchuk was young. Later, during his NHL career, it was any number of things. He’d see a movie and forget it wasn’t real. He’d be benched for a game and believe his friends on the team were behind it. He’d hear about an unfaithful spouse and be convinced that Sandra, his second wife, was cheating.

“That was a big one,” he says. “I don’t know if I can tell you anything more embarrassing than that. Is there some way you can sugarcoat it?”

•••

Most of the time, hockey was his escape. In 1982-83, he was the American Hockey League’s goaltender of the year. In ’85-86 with the Nordiques, his best NHL season, Malarchuk had four shutouts in 46 games and posted a 3.21 goals-against average. In 1989, with the Sabres, he was selected for the NHL All-Star Rendezvous tournament. Four times in his 10 big league seasons, he was named the NHL’s player of the week.

Whatever problems the OCD caused away from the rink, they vanished when the puck was dropped. For a while.

“The hell I went through before the games was awful,” he says. “But I loved the games. Nothing bothered me then. I was always able to turn things off, turn the world off, through hockey.”

But by January ’92, even the games didn’t help. By then, his off-ice obsessions were carrying over into uniform. Guarding the net in the NHL is stressful enough; guarding the net in the NHL while you obsess about adultery is terrifying. And guarding the net in the NHL while you obsess about adultery after two solid weeks of unceasing insomnia … is tantamout to suicide.

“This was a very serious case,” Stahl says. “Clint obsessed about his physical well-being, about whether or not his muscle movements were perfect. And he was worried about his wife. He had a completely unjustified belief that she was seeing other men.”

In ’92, Malarchuk didn’t sleep from the middle of January ‘til Super Bowl weekend, when the Bills played the Redskins. The game was big news in Buffalo, so some of the Sabres had a party to watch it. Already on painkillers and other medication for a bleeding ulcer his anxiety had caused, Malarchuk was desperate for sleep. His pill bottle came with the usual warning, “Do not take with alcohol.” To a twisted mind, the combination might induce drowsiness.

THE SPORTING NEWS 1994-95 Hockey Guide, under Malarchuk’s career notes, says he missed six games in January and February 1992 because of a “medicine reaction.” We sugarcoated that. The beers, the painkillers, the ulcer medicine and — later, at home — the scotch induced more than drowsiness. They induced a heart stoppage. No pulse.

They induced intensive care, which saved his life.

“He’d told me his stomach was bugging him, but this really kind of sprung up on us,” says Stars defenseman Grant Ledyard, Malarchuk’s teammate in Washington and Buffalo (they were traded together to the Sabres in 1991). “I think he figured, ‘Well, this is one way to get to sleep.’ It kind of backfired on him. He regretted it right away. But it was a big surprise to the team.”

Malarchuk says he dropped the booze-and-drug depth charge that night simply for relief. Some of his friends, privately, aren’t so certain it wasn’t a suicide attempt. In either case, it was a turning point in that the incident brought his illness into the open. Word was creeping out that Malarchuk was an overdosing drug abuser; going public with his obsessive-compulsive disorder, as distasteful as that was, sounded like the lesser of two evils.

Many OCD sufferers are so ashamed of the illness that they keep it secret; and, in fact, one of its oddities is that a person often can function through an eight-hour work day without displaying symptoms. The experts say people with the illness are the world’s best actors, because they suffer in silence.

So until Super Bowl Sunday 1992, his teammates knew Malarchuk as the joke-cracking master of ceremonies at fellow goaltender Daren Puppa’s wedding. They knew him as the singing cowboy at Christmastime in Buffalo’s Children’s Hospital, where he brought his Stetson and his guitar and went from room to room croaking carols and calling himself Clint Black. They knew him as the extroverted Canadian who, in a receiving line at the White House after an exhibition game between the Capitals and the 1988 U.S. Olympic hockey team, kept flipping the radio plug out of a Secret Serviceman’s ear, took off his shoe, held it up to his mouth and said, “Can you hear me?”

Then he struck up a conversation with another old actor.

“Oh, hi. Hey, I really enjoyed your dusters (Western movies). I still see ’em on TV once in a while,” Malarchuk said.

“Oh, you know, I really enjoyed making those,” Ronald Reagan said.

“Yeah, I bet it was a lot better than that clown thing you did,” Malarchuk said.

“Yeah, you know, I’m a cowboy at heart. I have a ranch and I love riding,” Reagan said.

“Tell me. Did you ever give that Barbara Stanwyck a run for it?” Malarchuk said.

“No, but I sure would’ve liked to,” said the President of the United States.

That’s Malarchuk’s recollection of the conversation, anyway. And if every word of it were true, it wouldn’t surprise his friends, most of whom know him as the gifted goaltender who fights a lifelong battle with OCD.

“He is such a great person to have around the room,” Reichert says. “He’s got the biggest heart in the world, and he’s a funny son of a bitch. I’ve never seen him turn anybody away. He’s as loyal as they come. If he’s your friend, he’s your friend for life. That probably got him in trouble a bunch of times, too, because with women, he’s loyal right to the end. I mean, he’d dig into his pocket and do whatever he had to do; and then he couldn’t understand how if he took care of everybody, why they couldn’t take care of him back.

“But at night, who knows what loneliness runs in his heart? I know some nights, he would change from Dr. Jekyll to Mr. Hyde. It was unbelievable. The only way I can explain it is what he always said about it He always said it was like there was a demon inside him that would make him think of weird stuff and he thought it was real. He’d say, ‘It’s like something just takes over inside me.’ It was really strange. He can put on a good show, but there’s still a ton of emptiness in the guy. I know that.”

Malarchuk touched bottom, or at least the latest level of it, about two years ago in San Diego, when, against Dudley’s better judgment, he put him in goal for the Gulls. By the time he had faced five shots, he’d given up four goals. At the end of the first period, he asked out of the game. At the end of the game, he asked out of the career.

In Dudley’s office, with Gulls General Manager Don Waddell sitting in, Malarchuk tried to quit. Refusing that request, Dudley and Waddell instead promised him help and as much time off as he needed; and, for the first time in his long day’s journey into fright, he found doctors who knew exactly what to do. Rice, the Gulls’ team physician, put him in touch with Dr. Stahl.

Stahl introduced him to Zoloft and behavior therapy. It took six weeks for the drug-induced diarrhea and nausea to abate. It took longer than that for the depression to lift.

“I wouldn’t leave my room,” Malarchuk says. “When I did leave my room, I wouldn’t leave the house. My wife hated me at the time. She thought I was a baby. She’d say, ‘Why are you crying?’, and I’d say, ‘I don’t know.’ She’d just shake her head and walk away, and then I’d cry even more. She wasn’t letting me see my son (Jed, now 2). It was total hatred, and I was drinking. I wasn’t drinking like a party guy, either. I was drinking to kill pain. I felt like a total loser — two marriages down the tubes and I didn’t know what I was going to do for hockey. It seemed like the only time I could smile was when I had a few pints in me. Plus, right about then was when I found out Kelli’s mother (his first wife) was taking her to Australia. Really, the only time I could smile was when I was drunk.”

Eventually, though, the Zoloft worked its magic. Malarchuk finished the season with the Gulls, playing well enough to share the James Norris Memorial Trophy (with San Diego teammate Rick Knickle) as the IHL’s best goaltenders.

When San Diego affiliated with the Mighty Ducks, though, Malarchuk was out of a job again. The Ducks wanted their own developmental goalies in San Diego, which put Malarchuk and Kelli on the highway to Las Vegas and a $40,000, one-year contract.

Nobody in Vegas has seen even a shadow of the OCD in the 18 months Malarchuk has been there. He played so well in ’93-94 that three months into his first season with the Thunder — his first healthy season in forever — he signed another four-year contract. His bonus for signing the new deal was two horses, and the contract calls for the team to provide him with another horse each season he plays.

The IHL, according to Thunder G.M. Bob Strumm, called to inquire about the breeding of the horses. Apparently, the league wanted to make certain these weren’t Kentucky Derby-quality nags that would escalate the worth of the contract.

“You know, Clint has gone through a couple of divorces,” Strumm says. “He made the comment at the time that if he ever had to split the horses up, he knew which end he’d give his ex-wife. The guy has totally stabilized his life. He’s found people he can rely on and teammates he can rely on. He’s been a guy who has accepted all the challenges we can give him, on and off the ice. He’s just been terrific.

“We didn’t rush into giving him this opportunity here, either. I mean, we did a lot of research. But there was just a gut feeling about the guy. He’s just a down-to-earth, straight-speaking, boot-stomping type of guy. Those are the guys you win with, or at least build with.”

•••

This season, Malarchuk splits time in goal with Pokey Reddick, another veteran with NHL experience (Florida, Edmonton and Winnipeg). That isn’t the way he’d prefer it, but it’s hardly an issue over which to obsess.

Besides, the emus demand more and more of his attention these days. There’s all that reading to do — how many other athletes keep copies of periodicals such as “Animals Exotic and Small” and “Ratite Marketplace” around the house? — and all that shiny future to plan. (FYI: Webster’s calls ratite an adjective, designating a flightless bird, as the ostrich or emu, having a flat breastbone without the keel-like prominence characteristic of most flying birds.) Someday soon, the way Malarchuk figures it, the market for emu oil, which apparently has applications both as a cosmetic and an anti-inflammatory lotion, will explode. He’ll be on the cutting edge.

As for hockey, he just may play until he’s 38, even if Vegas isn’t the NHL.

“The way things are now, it would take a lot to get me away from here,” he says. “Deep down, to get back to the NHL is certainly very attractive. I worked my whole life to get there, and I spent 10 years there. I’ve often laid awake in bed, thinking of going back and being a comeback player, winning the Bill Masterson Trophy for perseverance and dedication to hockey.

“But really, my only reason for going back there would be to prove to the public, prove to the NHL people who I think sort of blacklisted me because of the obsessive-compulsive disorder, that I could do it. And I don’t think I want to throw away a four-year deal here on one year in the NHL. I start looking at what I have here in Vegas; and it’s a pretty nice feeling going to bed at night, knowing I have them. You know, Christy is the first normal relationship I’ve ever had.”

Home happens in strange ways sometimes. The important thing in Malarchuk’s case is that it happened at all. Finally.

Sidebar: The distant replay

This story, by senior writer Michael Knisley, first appeared in the March 6, 1995, issue of The Sporting News, as a sidebar to a larger story about Clint Malarchuk, who as the Sabres’ goalie on March 22, 1989, suffered a near-fatal injury when his jugular vein was slashed by an opposing player’s skate.

“I’ve got a videotape,” Clint Malarchuk says. “Let’s watch it, OK?”

So there it is from three different angles, in living (and nearly dying) color: The Blues’ Steve Tuttle and a Sabres defender at full tilt, approaching the net, colliding with Malarchuk, Tuttle’s skate blade severing Malarchuk’s jugular vein, blood gushing several feet onto the ice with every beat of his heart.

The voice of the play-by-play man nearly breaks down, then almost-comically he remembers his job. “Oh, God,” he says. “Oh, God. Please, take the camera off this. Don’t even bring it over there, please. Just keep it away. My God, what happened? Oh this is terrible. You’re watching Sabres hockey.”

We sit in Malarchuk’s living room with his daughter, Kelli. The videotape shows Malarchuk clutch his neck, look up at an official as the pool of blood grows and mouth the words, “Am I going to live?”

The four-inch scar is still plainly visible on Malarchuk’s neck, as he talks about how he learned later that a number of fans in the stands and restrooms passed out that night in Buffalo, March 22, 1989.

“Why did people pass out, Daddy?” Kelli says.

“Well, it was gross,” Malarchuk says. “There was a lot of blood.”

As Malarchuk recounts the story of how they helped him off the ice, packed pressure onto his neck and saved his life, the videotape shows Sabres defenseman Grant Ledyard, his teammate in Buffalo and Washington, banging his stick against the boards in frustration. Ledyard and Malarchuk had been traded together to the Sabres on March 6 that season, a little more than two weeks before that game against the Blues.

“I honestly thought he was dead,” Ledyard says. “I went absolutely bananas on the ice. It was not a very fun situation at all. I don’t watch that tape very often. If it’s on, I might peek at it. But I would never volunteer to put it on for anybody. If I have a chance to watch it, I won’t do it.”

Neither will I.

Read the full article here