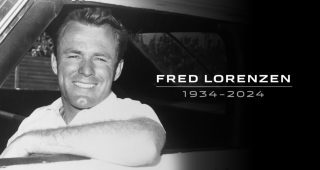

Fred Lorenzen, a thinking man’s racer who became one of NASCAR’s biggest money winners during the sport’s rise in the 1960s, has died. The NASCAR Hall of Famer was 89.

Lorenzen’s passing was confirmed by his family. The former driver had battled dementia in his later years.

Lorenzen won 26 times in his premier-series career, vaulting to stardom after connecting with the powerful Holman-Moody Ford factory team in the early part of the decade. Many of those victories arrived as both speedways and purses grew in size, and he became the first driver in NASCAR to earn more than $100,000 in a single season in 1963. Among those prized wins were the Daytona 500 in 1965 and two victories in the Coca-Cola 600 at Charlotte Motor Speedway.

RELATED: Fred Lorenzen: NASCAR Hall of Fame Class of 2015

“Fred Lorenzen was one of NASCAR‘s first true superstars. A fan favorite, he helped NASCAR expand from its original roots,” NASCAR Chairman & CEO Jim France said. “Fred was the picture-perfect NASCAR star, helping to bring the sport to the silver screen — which further grew NASCAR‘s popularity during its early years. For many years, NASCAR‘s “Golden Boy” was also its gold standard, a fact that eventually led him to the sport‘s pinnacle, a rightful place in the NASCAR Hall of Fame. On behalf of the France family and all of NASCAR, I want to offer our condolences to the friends and family of Fred Lorenzen.”

Lorenzen went by many nicknames, known as NASCAR’s “Golden Boy” for his dashing looks. His charm, combined with his racing success, led him to win the series’ Most Popular Driver Award on two occasions.

He was also called the “Elmhurst Express” in a nod to his Illinois hometown, in addition to the alliterative “Fast Freddie” or “Fearless Freddie.” But those nicknames belied a smooth, measured approach that was in sharp contrast to go-for-broke predecessors, such as Junior Johnson and Curtis Turner.

Frederick Lorenzen Jr. was born Dec. 30, 1934, growing up in the suburban Illinois town of Elmhurst, about 20 miles west of the Chicago Loop. He was drawn to stock car racing at first by listening to broadcasts during backyard campouts or on his father’s car radio. His first competitive driving experience came in drag racing at age 19. When not racing, carpentry was his trade.

After four years of straight-line competition, Lorenzen turned to oval tracks, making his NASCAR debut in 1956. After a fruitless seven-race stint in his own equipment, he soon turned to driving in the rival U.S. Auto Club (USAC) Stock Car division. He won 12 times in USAC competition, claiming the series championship in back-to-back seasons in 1958-59. Meanwhile, Lorenzen was becoming a regular winner at O’Hare Stadium’s quarter-mile oval near his hometown, and the lure of a NASCAR return became strong.

“I had an important decision to make — to stick with USAC and eventually get into the big race at Indianapolis or join NASCAR, the world’s largest auto race organization which specializes in stock-car events,” Lorenzen told the Arlington Heights Herald in July 1960. “Since stock cars are the type of racing I know the most about and since NASCAR’s prize monies are the highest anywhere, I made my change. Up to now, however, I must admit that I had begun wondering if I had made the right move and if I was actually good enough for NASCAR.”

His performance that year during his venture south helped to prove his worth, as he netted top-five finishes in a pair of races at Daytona International Speedway and one at Atlanta Motor Speedway in his own equipment. Lorenzen’s results in both series sparked interest from other car owners, but so did his studious approach to the sport.

Other teams mocked his insistence on pit-stop coaching and drills during an era when the practice was uncommon, but that emphasis paid off with quicker service and positions gained during the race.

“(Other drivers) partied, they were out to go fast and live the life, but when my dad came in, he was business,” daughter Amanda Lorenzen Gardstrom said in a 2014 interview. “… After every time he won a race, he’d call the stock broker and want to know the best way to invest that. He insisted that his pit crew was ready to go at 7 o’clock in the morning every day — clean white suits and ready to work. They all worked, and they planned and had strategies as a team.”

Said Herb Nab, later his chief mechanic: “Freddie was a stickler. He worried about everything. He wanted everything to be just so. He was never satisfied unless it was. Maybe that was the key to his success. He wanted perfection, and he made sure he got it.”

Lorenzen had already moved his family south to Charlotte, North Carolina, before the 1960 season, connecting with team owners John Holman and Ralph Moody to aid his racing efforts in NASCAR. A phone call on Christmas Eve changed his career arc, with the invitation to compete for Holman-Moody full-time, becoming one of the centerpiece drivers for Ford’s factory effort.

“Biggest day of my life. A miracle, that’s what it was,” Lorenzen told TNT Sports in 2009. “Everybody waits for this, but you make your own way. I earned it, I guess. That’s what Ralph (Moody) said, you’re here because they want you. They like the way you ran it, the way you drive. You don’t jump out front, you just cool it and wait, take your time.”

Holman’s son, Lee, said Lorenzen was a natural fit with the Holman-Moody operation, known for its meticulous attention to detail.

“All he’d ever done is race,” Lee Holman told NASCAR.com in 2014. “He was a famous Illinois dirt-tracker before he came to us and had done real well in other series, so it wasn’t like we trained him and made him what he was. We just gave him an opportunity to move into NASCAR.”

Lorenzen wasted little time getting acclimated to his new surroundings, winning three times and netting four pole positions in his 15 starts in 1961. Holman-Moody focused on NASCAR’s larger and higher-paying events, so Lorenzen never ran a full campaign at the Cup Series level in his pearly white No. 28 entry; the closest he came was participation in 29 of 55 events in 1963, when he won six races and became the first driver to break the six-figure mark in prize money in a single season.

By the time he assembled an eight-win season in 1964, which included a stretch of five consecutive victories and a grand slam at NASCAR’s four biggest speedways at the time, Lorenzen had gone from a promising newcomer to one of the sport’s most compelling stars. Though he was considered by some to be an outsider because of his northern roots, Lorenzen quickly earned the respect of established stock-car racing peers.

“Certainly, Freddie is for real, and I have nothing but praise for him,” Hall of Famer Fireball Roberts told The Charlotte News in May 1964. “He has so many things going for him as well as luck which you must have in this business. First, Freddie has the finest machinery. He also has splendid mechanics in Herb Nab and Wayne Mills, who know how to set up a car. But the man who makes this team go is Lorenzen.”

Lorenzen’s legend on NASCAR’s largest tracks was already established by the time he prevailed in the “Great American Race” in 1965, claiming the first rain-shortened Daytona 500. He drove away from late contact with Marvin Panch as a shower sprang up on the backstretch, staying in front when more rain halted the event after 133 of the scheduled 200 laps.

Though he kept plucking wins at a substantial clip, Lorenzen’s career began to slow the next two seasons. In 1966, Ford’s boycott of NASCAR’s engine rules limited Lorenzen to just 11 starts. The next season, Lorenzen made just five appearances before abruptly retiring on April 24 at just 32 years old, battling health issues and tiring of the racing circuit’s travel demands.

“I guess every athlete wants to quit when he’s on top,” Lorenzen told the crowd gathered as a retirement banquet thrown by Ford’s racing division. “I know I’m slowing down and have been a little more cautious in the last year and a half. Plus I haven’t been feeling too well lately. The ulcer is a small one, but it sure takes a lot out of you. I added up all these things and decided that now was the time to quit.”

Lorenzen had invested much of his prize money and endorsement revenue, and he remained active in the stock market. He also stayed busy by offering occasional help to Holman-Moody and car owner Bondy Long, working as a realtor and making his movie-screen debut playing himself in the campy 1968 film, “The Speed Lovers.”

But the draw of competition remained strong with Lorenzen, who hinted in November 1969 that he might attempt a return. His comeback race was the next year’s World 600, which he led for 47 laps before the engine let go on his Richard Howard-owned Dodge.

“The day I quit I said I knew I’d be back someday,” Lorenzen said, also admitting, “I think I waited too long.”

Lorenzen’s return spanned 29 races from 1970-72. He claimed two pole positions, but the closest he came to winning was a runner-up finish at Dover International Speedway in 1971. That return was marred by heavy crashes at Darlington Raceway and the former Ontario Motor Speedway, plus a head-on highway accident that injured Lorenzen and his father and killed the other driver in January 1971. A final comeback attempt with the Wood Brothers at Darlington resulted in a severe wreck in testing. His second retirement stuck after his dissatisfaction with some of his Hoss Ellington-led crew boiled over before Charlotte’s 500-miler.

“I had gone to the track before 8 a.m. My crew wasn’t there,” Lorenzen later recalled to Bob Myers of The Charlotte News. “Others teased me that they’d been in a lounge partying all night. I just couldn’t tolerate mixing business with pleasure or the razzing. I had not won in 30 races. I had lost my Holman and Moody crew. The driver cannot do it alone. I got disgusted and left.”

Lorenzen continued as a top-earning realtor in the Chicago area after his driving days. Even in retirement, the racing accolades kept coming — he was inducted into the National Motorsports Press Association in 1978, the International Motorsports Hall of Fame in 1991 and the NASCAR Hall of Fame in 2015.

As his health declined and his memory loss advanced in his later years, Lorenzen became the second known driver to pledge his brain in 2016 to the Concussion Legacy Foundation and Boston University, both leading partners in the research of concussions among athletes and chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a degenerative brain disease. Lorenzen’s family drew inspiration from Dale Earnhardt Jr.’s decision to do the same weeks earlier and his advocacy for neurological health.

It’s another layer in the legacy of a Golden Boy from a golden era, one whose popularity endures.

“The fans are what make you run, and they were my heroes. They make you go fast,” Lorenzen told TNT in 2009. “It was a dream come true. All the work you did all your life, it’s something you can’t describe.”

Read the full article here